Kaitlyn McGrath Jun 22, 2023

TORONTO — The Blue Jays charter plane had tried to land twice. The weather was bad in the Boston area, wet and foggy. If the third attempt failed, they were going to have to land somewhere else.

Nobody wanted that, especially not after the day they’d had. The mood inside the plane was tense following a disappointing loss to the Seattle Mariners and the aborted landings. Everyone was just about fed up.

Thankfully, on the third try, the plane landed safely. The whole team cheered, all relieved, happy and ready to get to their hotel. But they had to wait to disembark. For an hour.

So, Matt Chapman grabbed a microphone. He turned on the team’s stereo and kicked off a karaoke show right then and there. The Blue Jays third baseman belted out a few songs. The reviews? “He can sing pretty well,” said outfielder Daulton Varsho. (Chapman’s mom, Lisa, and sister, Haley, are singers, so carrying a tune is in his DNA.) After Chapman’s performance, the microphone was passed to center fielder Kevin Kiermaier and pretty soon the entire team — and even, at one point, an airport security guard — was involved. The karaoke party continued onto the bus until the team finally reached the hotel in the middle of the night.

“We could have totally all just been super pissed off,” Chapman said of the travel mishap. Instead, the Blue Jays ended up having a blast. It was no surprise that Chapman was at the center of it all.

“He knows how to lighten up the mood,” Varsho said, “and have a good time.”

Chapman is the team DJ, hype-man and comedian rolled into a 6-foot, 215-pound package. His one-liners keep the clubhouse loose, but games are no joke.

“He’s night-and-day different once the game starts,” said Toronto starter Kevin Gausman.

Once an energetic kid from Southern California, “Chappy”— a nickname he’s had since college — found his place on a baseball field early and grew from an undersized, undrafted high schooler to one of the game’s premier third basemen, all while accumulating praise for being the teammate everyone wants beside them.

Chapman spent five seasons with the Oakland A’s, transitioning from a talented rookie to an All-Star. He was part of a successful core, which included the ultra-serious Marcus Semien and the laid-back Matt Olson. “There had to be some times where I had to pull the reins on Chappy,” said Olson, now with the Braves, “and he had to fire me up, but it was a good little combo we had.”

As Chapman’s former team visits Toronto this weekend, the Blue Jays are entering a crucial time to try to gain ground in the standings. It’s been an inconsistent season, but with the club still in the mix for a wild-card spot nearing the season’s halfway mark, they’ll be looking at Chapman to help lead them through a playoff push with his leadership both on and off the field.

“He’s not like any other teammate I’ve ever had,” said Blue Jays second baseman Whit Merrifield. “He’s off the wall. You never know what he’s going to say but he just keeps it fun, keeps it light — and, at the same time, he’s a hell of a player.”

All Chapman ever wanted to do as a kid was play under the sun in the cul-de-sac he grew up on in Lake Forest, Calif. And, inevitably, after every intense round of outdoor play, the energetic Chapman would come back into the house sweaty and exhausted.

“We used to always say he’s not sleeping, he’s recharging,” his dad, Jim, said.

Baseball, hockey, lacrosse, whatever game he was playing, Chapman was intent on winning, even when he was with friends and his mom, Lisa, tried to explain that these games were just for fun.

“He would have a fit if he wasn’t winning,” Jim said. “He was just playing so hard. These other kids, they couldn’t keep up.”

Baseball was the game he loved most and on the field, he said, he could always find his focus. He dreamed of one day being a professional player, so from a young age, he wanted to look the part. Before games, he’d borrow his dad’s sunglasses to put on top of his hat. He wore eye black, had sweatbands on both of his wrists and wore chains around his neck.

“It was like he was dressed up for Halloween to be a professional baseball player,” said Mike Gonzales, who first met him when Chapman was 12 years old and later coached him at El Toro High School.

Chapman was a skinny kid, but he excelled on the field. He started out as a catcher, but by the time he was 11, his dad, who doubled as his coach, moved him to shortstop, typically where the most talented players go. On his elite travel ball team, he played second base. While he didn’t hit for much power back then, he got on base and could run a little. His edge, though, was his defense.

“He became such a good defender that you couldn’t take him out of the lineup. He was too valuable,” his dad said.

While at El Toro High School, Chapman famously played alongside fellow future MLB third baseman Nolan Arenado. (Both their numbers — No. 12 and No. 6 — have been retired and hang on the school’s outfield fence). Chapman was two grades younger, so he was a backup shortstop and would DH when Arenado started, and play shortstop when Arenado pitched. Chapman took note of how dedicated Arenado was, coming to the field early to hit or take extra ground balls with him. Naturally, their drills would sometimes turn into a friendly competition.

“To see the way those guys work, they weren’t very happy if they made a bad throw or missed a ball,” Gonzales remembered.

Even as a high schooler, Chapman was serious about his craft, preparing and playing with a professional-like intensity. But outside of competition, he was known for ribbing his teammates as a form of friendly motivation. “He always wanted to get the last word in,” said Gonzales, who added his teammates knew the trash talk was good fun. “When the game time came, he was 100 percent behind his own teammates, and they knew that.”

When Chapman was a senior — and the starting shortstop — he got exposed to plenty of MLB scouts. After years of being a wiry kid who couldn’t grow a moustache like the rest of his buddies, he finally hit his growth spurt heading into his junior year and started filling out his 6-foot frame. But while talented, Chapman wasn’t quite “physically ready” to be in professional baseball, said Eric Martins, the Oakland A’s third base coach who scouted Chapman and has known him since he was a child.

Chapman’s dad knew he wasn’t ready, too. So, unbeknownst to his son, Jim shooed away MLB offers. After Chapman wasn’t drafted, he said he felt overlooked by MLB scouts and carried that with him for a while, but he had a scholarship to play at Cal State Fullerton, a local Division I program, where he was once a bat boy. It was a dream alternative.

In college, Chapman learned to take care of his body, eating right and lifting weights. Finally, he looked like a man, not the “twig” he used to be, he said. He also met some of his best friends at college, many of whom would go on to be groomsmen at his wedding. “We had a blast,” Chapman said of those years. Meanwhile, on the field, before his junior year, he switched to third base, a career-making move.

“I don’t think that I was mature enough to go off into the minor leagues (after high school) and be a professional right away. I needed to be a kid still and mess up a little bit,” he said, admitting that he’s now grateful for what his dad did. “I’m just super glad it worked out.”

Continued in comments.

One summer during college, Chapman played for the United States collegiate team. Most of the team, including future MLBers Alex Bregman, Kyle Schwarber and Trea Turner, received invites to join. Chapman had to try out. He flew to Cary, N.C., and impressed the coaches with his work ethic that he made the team as the starting third baseman.

It was an ah-ha moment for Chapman, a realization that his path was indeed leading toward an MLB future. During the tournament in Japan, Chapman even dabbled in pitching, hitting 99 mph on the radar gun while racking up three strikeouts in two appearances. After that, he decided he’d better not pitch anymore or “they might try to turn me into a pitcher,” he said.

After three years at Cal State Fullerton, Chapman was on the A’s radar. After missing the team’s pre-draft workout because of college playoffs, the A’s invited him to a private showcase at the Oakland Coliseum. Before he boarded his flight, Chapman told his dad: “I’m going to kill it.”

The A’s top executives, including Billy Beane and David Forst, watched Chapman take a few ground balls at third, but everyone already knew he could play defense. Martins had already told the A’s scouting department, “If we drafted him, we could start him at third base and … he’d be in the running for a Gold Glove.”

But the team was unsure of his power because he’d hit only 13 home runs in college. When it was time to take batting practice, Chapman grabbed a random wood bat that belonged to then-A’s outfielder Josh Reddick because it felt “kind of like a metal bat,” Chapman said.

When it was time to hit, Chapman started hammering line drives. The first one bounced and hit the wall. The next couple hit the outfield walls. “Then he let a few go and then it was just like, OK, well, we see the raw power,” said Martins, who had texted Chapman’s dad and told him his son was “putting on a show.”

Soon after, the A’s drafted Chapman as the 25th overall pick in 2014.

And that random bat he picked up? It’s still the Old Hickory model Chapman uses today.

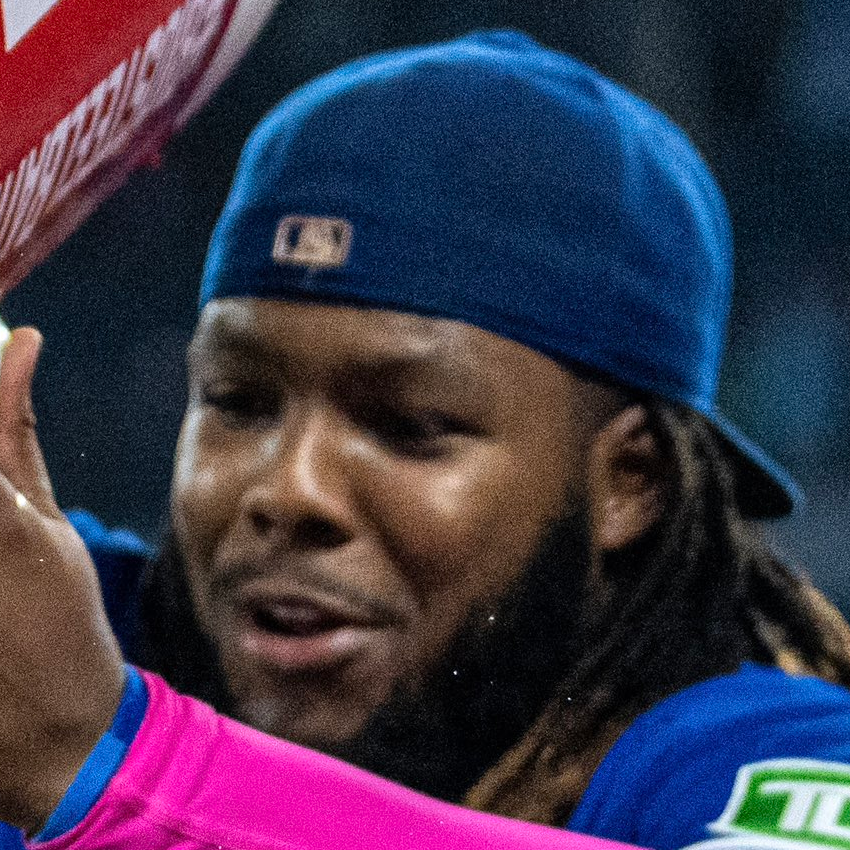

“Thank you, Josh Reddick,” Chapman said. Defense has long been a strength for Chapman, and he “believes he should get to every ball.” (Sam Hodde / Getty Images)

In the hours before a game, when the media is granted access to the clubhouse, it’s rare to see Chapman sitting still for very long. The 30-year-old, usually wearing a T-shirt with the sleeves cut off, spends his time bouncing between the clubhouse, weight room, batting cages and field.

“He never misses a day,” said right fielder George Springer of his pregame routine.

When he takes ground balls at third, Chapman approaches it with game-like intensity, but leaves space for flair, maybe transferring a ball between his legs before making a crisp throw. He has a natural aptitude for fielding and footwork, but his strong arm is a product of good genes — his dad, Jim, who played in college, had a great arm, too — and nightly games of catch. He honed his daredevil dives while playing on the street and having to prevent balls from denting nearby parked cars. “Just from saving some of my buddies’ bad throws,” Chapman said.

Pitchers will tell you they relax when they see a ball hit toward third because of Chapman’s range, on-target throws and steely calm even in high-leverage moments. “He believes he should get to every ball,” Gausman said. “There’s been so many times a ball hit 110 (mph) right by him and he’s like, ‘Man, I’m sorry, like I should have had that.’”

Even with five Gold and Platinum Gloves, Chapman remains as thorough as ever with his preparation. During a defensive drill this past spring training, for example, he asked manager John Schneider if he could borrow his phone. He wanted to text himself a message.

“I was like, ‘About what?’” his manager asked him. “And he said, about his pre-pitch setup, because he didn’t want to forget it. When you listen to a guy who has been so good, in the middle of February, talking about where his foot was planting on a fungo from (third base coach) Luis (Rivera), you’re like, all right, dude, that’s why you’re good.”

When batting practice begins, Chapman shows off his power, reaching the upper decks of the Rogers Centre. “I didn’t realize how strong he was,” Kiermaier said. Chapman introduced a toe-tap into his swing mechanics this season, helping with his rhythm at the plate, and that led to an otherworldly April, where he hit .384/.465/.687 with 20 extra-base hits and a 218 wRC+ (where 100 is league average). That won him his first Player of the Month award. His numbers, however, have fallen off since. Before play on Wednesday, he was managing just a 64 wRC+ since May 1. The real Chapman is likely somewhere between those two extremes, and following back-to-back two-hit games against Miami, there are signs Chapman is finding his swing again. For the Blue Jays’ offense to get back on track, and for this year to end as fun as it began, they’ll need him to rediscover his power stroke.

When the A’s started dismantling their roster after the 2021 season, Chapman was traded to the Blue Jays in March of 2022, just as the shortened spring was getting underway. It was a whirlwind, and it took him awhile to adjust to his new team. A natural-born leader, he hung back in his first few months, not wanting to insert himself before he had earned his teammates’ respect. But by summer, his slow start behind him, he was comfortable speaking up more in the clubhouse. And after an offseason spent discussing with Schneider ways he could lead, Chapman is at the center of off-field activities, such as the recent travel day where the team dressed like Chappy — meaning, flowery button-up shirts or Chapman jerseys.

“I think his words were, you can count on me to take the next step in that category,” Schneider said.

Asked what he brings to the team, nearly all his teammates used the same word: “Energy.”

“Energy on and off the field,” said shortstop Bo Bichette. “I think on the field he’s always prepared. He competes, he has a lot of confidence. … Off the field, I think he brings a lot of camaraderie. He gets the team together.”

Chapman can be counted on to lead postgame celebrations, too, no matter his nightly performance. Ryan Christenson, the former A’s bench coach who is now the associate manager with San Diego, remembered when former A’s starter Mike Fiers threw his no-hitter in May 2019. Even though Chapman went 0-for-4 with four strikeouts, “he was the guy that was there celebrating Mike’s accomplishment and leading the charge. I just always admired that about him,” Christenson said.

As the self-appointed team DJ, Chapman’s music tastes range widely, from classic to psychedelic rock to hip-hop, rap and techno. Does he take requests? “Not really,” said Gausman. “I wish he did. Some days it’s pretty bad.” But he loves it, so his teammates let him do it. “Nobody can take it from him,” Gausman said.

And while Chapman might be the first guy to crack a joke, he’s also quick to share an encouraging word for a slumping teammate or a back pat for a pitcher who just issued a walk. For example, after losing Game 1 of the Wild Card Series last year against Seattle, Alek Manoah sat hunched over at his locker. Chapman leaned over, put his arms around him and said, “I know you’re not happy with how you played today, but we wouldn’t have been here without you.”

“It was good to hear in the moment,” Manoah said. “Especially from somebody that everybody kind of holds his words with a lot of weight.”

Kiermaier calls Chapman a positive reinforcement coach. “He loves his teammates. It doesn’t matter who you are, what you’ve done. If you’re wearing the same jersey as him, he’s going to respect you and he’s going to root for you,” Kiermaier said. “And so those are the types of guys you want on a team and I’m a huge, huge fan.”

At times, frustration had crept into some of Chapman’s at-bats during his offensive struggles of the past month and a half, but as he tries to emerge from the slump, and as the Blue Jays wade through another inconsistent season, Chapman continues to balance his dual sides: the serious gamer on the field and the even-keel glue guy who keeps spirits high in the room, win or lose.

“If you want to be a true leader,” Chapman said, “it can’t all just be about you showing up, doing your work. You have to be all-in on the team.”